Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is an absorbing, stylish character study, a film overflowing with complex emotions: love, loss, aging, friendship and betrayal, the confusions of political change, but most of all nostalgia, an aching, bittersweet nostalgia for a more innocent time that may never even have existed outside of the movies. Nevertheless, the film's titular Colonel Blimp — the nickname of Clive Candy (Roger Livesey), who matures during the film from a volatile young soldier into an aging, rotund, well-respected general — is indubitably a representative of that more innocent time. He is an embodiment of the English gentleman, with all that entails, for both good and bad. He is stiff and elitist, with a great respect for rules and procedures, for protocol. He's condescending and imperialist, unquestioning of his own country in all that they do. But he's also kind-hearted and generous, the kind of man who will fight a duel and then become best friends with his opponent afterward.

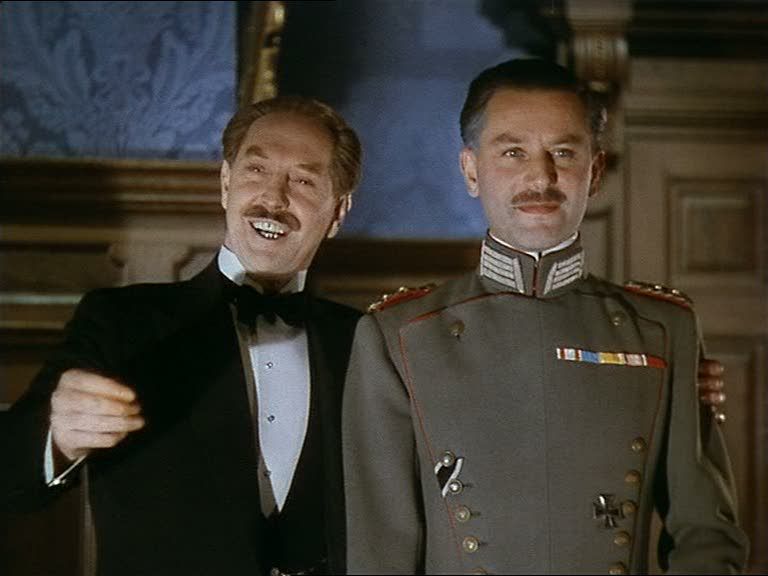

This is exactly what happens in the film's first extended segment, a reminiscence of Candy's time in Berlin during the early 1900s, where he has gone to defend his country's honor over accusations that the British had committed atrocities during the Boer War (which, of course, they did, though Candy doesn't know this and the film is politically unable to acknowledge it). Candy means well, but his blundering nearly causes an international incident when he, more or less inadvertently, insults the entire German army. The Germans pick an officer from their ranks to fight a duel against Candy, and when the two men wound each other, they are sent to the same hospital to recuperate. There, Candy becomes fast friends with the officer, Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook), despite the other man's lack of English. They communicate mostly through the lovely English governess Edith Hunter (Deborah Kerr), who in the process falls in love with Theo. This is the film's most detailed and evocative segment, and for good reason, since the events here will haunt the remainder of Candy's long life. His friendship with Theo will last, despite long absences when the two men do not see each other, and despite even the period of hostility when they fight on different sides during World War I. But Candy will be even more deeply scarred by his unrequited and, indeed, never pursued love for Edith, who stays behind in Berlin to marry Theo. Candy, always a gentleman, smiles broadly and congratulates his friend when he learns of the couple's engagement, but he is hurt nonetheless, and he returns to London feeling a great loss, a loss that will affect him for the rest of his life. He will continue looking for Edith everywhere he goes, and will find at least two more incarnations of her (both also played by Kerr).

This romantic, melancholy story is simply one thread weaving through Candy's long and eventful life. In between incidents, the film uses documents and objects to mark the passage of time: newspaper reports, photographs, letters, and especially the accumulation of animal heads in Candy's den, each one dated and stamped with the location where he shot it. Various deaths are noted in simple two-line obituaries, the entirety of a life reduced to a platitude in a newspaper — the exact opposite of this film's sprawling, generous storytelling. Even so, these interludes sometimes seem to elide too much. Candy's long and presumably happy marriage to Edith look-alike Barbara Wynne (Kerr again) is treated very superficially, and his wife's character is never allowed to develop very much beyond her resemblance to his first wife. One wonders if this is intentional, reflecting Candy's essential disinterest in her beyond her appearance. One gets this sense especially from a late scene, after her death, in which the much older Candy proudly shows off her portrait to Theo, mechanically repeating how much she looked like Edith.

In a way, though, it hardly matters, since despite the romance the real central relationship of the film is the one between Candy and Theo, who reconnect as old soldiers when the latter flees to England, escaping from the Nazi horrors in his own country. The relationship between these two men is complex, woven together with politics and with their mutual love for the same woman. One of the film's most interesting uses of time is the way it condenses the period of time between the two World Wars, so that Theo's departure from London as a defeated P.O.W. after World War I is swiftly followed by his return to London many years later as a refugee from the Nazis. In the first scene, he leaves offended by Candy's patronizing attitude towards him, and he angrily tells his fellow German soldiers about the weakness and naivete of Britain — an ominous suggestion of the post-WWI bitterness and bad feelings that would thrust the Nazis into power. By leaping over the intervening years, the film powerfully depicts how Theo's initial bitterness over losing the war had given way to a more resigned melancholy, as well as a hatred of the evil forces taking control within his own country.

This film was made at the height of World War II, so it should be no surprise that it contains elements of anti-German war propaganda. What's interesting is how subtly this material is incorporated into the narrative, and how sophisticated and twisty the film's messages about war and nationalism can be. Candy is a naïve figure, convinced of his own rightness and that of his country: he believes in fighting wars according to rules, maintaining strict decorum and gentlemanly conduct even in the midst of combat. A repeated theme throughout the film is Candy's obliviousness, his outdated outlook on the world, which persists even as those around him increasingly argue that they must respond to the aggressions of their enemies not as gentlemen but as unrestricted fighters who will do anything to win. One of the film's most interesting questions, then, is whether it's Candy or the filmmakers who are actually naïve — or if they just expect audiences to be naïve. The film repeatedly characterizes British fighting methods as decent and noble and pure while the methods of their enemies are characterized as dirty and cowardly. Beyond the obvious contradiction — the quaint fantasy of fighting a "decent war," as though so much bloodshed could ever be anything but horrible — this mentality willfully glosses over all sorts of historical facts about British warfare preceding World War I, which could hardly always be described as "noble."

Candy doesn't realize that his ideal of a gentleman's war is a fantasy. There are hints in the film of darker realities — one scene cuts away before a scarred soldier begins interrogating a group of German prisoners, but there's little doubt that things got ugly after the fade to black — but it's obvious that there couldn't be any more tacit acknowledgment of these kinds of things, not in a wartime propaganda drama. For the most part, this is a brightly colored Technicolor fantasia of Candy's worldview, nostalgic for a time when wars could be fought with honor. But as nostalgia goes, this is especially sumptuous and skillfully executed nostalgia, with gorgeous studio-bound Technicolor imagery, lushly painted matte backdrops standing in for sunsets and bombed-out wartime locales. The obvious artificiality of it all helps create the impression of war as a clean, honorable affair, a game between gentlemen, who set start and end times, in between which they bomb one another. The beautiful, textural cinematography (by George Périnal, with future Powell/Pressburger cinematographer Jack Cardiff assisting) is suited equally to sweeping, colorful vistas and enveloping closeups.

One of the best of these is an extended shot of Theo as a much older man, a long, carefully held closeup during which he tearfully recounts the story of his stay at the hospital in Berlin, where he met both his future wife and the friend who would remain his one constant throughout his life. The camera stoically studies his face, now lined and worn with age, his features softened by his bittersweet memories of the past, of this time when he was so happy. The rich emotions of this scene are deepened by the immersive quality of the closeup, and by the fact that these characters have grown and matured over the course of the film, aging slowly into their older incarnations. The makeup used to age them sometimes makes them look mummified, caked in white paint, but the subtlety and warmth of the performances always shine through. Candy could easily have been the oversized caricature implied by the film's title, a walking symbol of British obliviousness and elitist condescension. And he is, to some extent. But he's also a sympathetic, richly drawn character, a man left behind by history, a man whose private ideals are increasingly out of sync with both his nation and the world, if they were ever in sync with anything beyond his own fantasies to begin with.

0Awesome Comments!