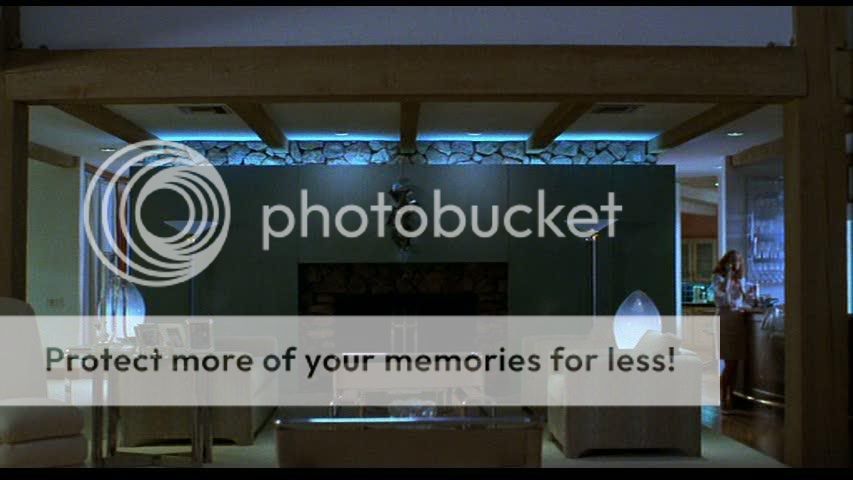

Todd Haynes' Safe is a creepy, oblique horror movie about the horror of the "normal" life. It's a horror film in which there is no creeping monster behind the sedate suburban façade, no locus of evil that preys on the frazzled housewife Carol (Julianne Moore). The suburbs themselves are the source of the horror here: the ornately empty houses, the bored chatter of housewives with no real interests and nothing to talk about, the antiseptic routines of daily life, the lack of connections even to her own family. For the gay Haynes, straight existence itself is terrifying, a hellish, deadened nothingness with few escape routes. The first half of this film, in which Carol is isolated within her own palatial home as though stumbling in a narcotic daze, is a kind of warm-up for the pastel-colored Sirkian mise en scène of Haynes' Far From Heaven, in which he channeled Sirk's brightly colored vision of suburban Americana and the social ills lurking underneath. Safe is more oblique than both Sirk himself and than Haynes' later Sirk pastiche. There's something chilly and suffocating about this film, in the weirdly distanced interiors, so carefully set-decorated and lit, their precise geometric contours and patterned colors isolating Carol within a space where nothing betrays a hint of life or motion or vitality. Haynes' camera simply sits at a distance, observing stoically as this ordinary woman comes apart at the seams, becoming convinced that her very environment is trying to poison her.

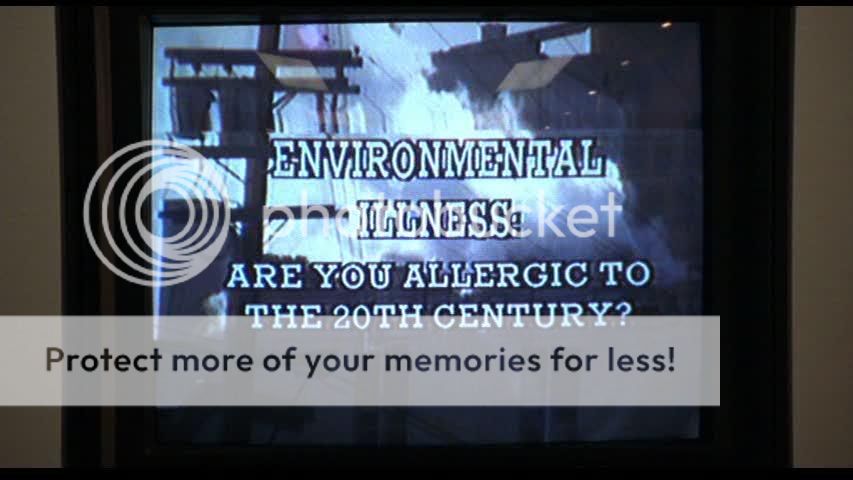

Todd Haynes' Safe is a creepy, oblique horror movie about the horror of the "normal" life. It's a horror film in which there is no creeping monster behind the sedate suburban façade, no locus of evil that preys on the frazzled housewife Carol (Julianne Moore). The suburbs themselves are the source of the horror here: the ornately empty houses, the bored chatter of housewives with no real interests and nothing to talk about, the antiseptic routines of daily life, the lack of connections even to her own family. For the gay Haynes, straight existence itself is terrifying, a hellish, deadened nothingness with few escape routes. The first half of this film, in which Carol is isolated within her own palatial home as though stumbling in a narcotic daze, is a kind of warm-up for the pastel-colored Sirkian mise en scène of Haynes' Far From Heaven, in which he channeled Sirk's brightly colored vision of suburban Americana and the social ills lurking underneath. Safe is more oblique than both Sirk himself and than Haynes' later Sirk pastiche. There's something chilly and suffocating about this film, in the weirdly distanced interiors, so carefully set-decorated and lit, their precise geometric contours and patterned colors isolating Carol within a space where nothing betrays a hint of life or motion or vitality. Haynes' camera simply sits at a distance, observing stoically as this ordinary woman comes apart at the seams, becoming convinced that her very environment is trying to poison her.The second half of the film largely abandons this stylized suburban crypt as Carol checks herself into a New Agey treatment facility that deals with amorphous illnesses caused by environmental factors. There, the urbanely sinister guru Peter Dunning (Peter Friedman) dispenses a variety of arcane "cures" and self-help advice to his patients. Haynes is not-so-subtly mocking the various charlatans and hippie commune-type facilities that exist on the fringes of this kind of Californian lifestyle, and especially the empty promises and rhetoric of so-called AIDS "cures." Carol, fleeing from the monotony of her zombified home life, winds up somewhere even worse, alienated even from her family, truly alone. By the film's end, she's locking herself up in a containment chamber where she can retreat from the world and try to come to terms with whatever her mysterious illness might be. With its halved structure, Safe asks whether the cure might sometimes be worse than the disease, or whether there is really any escape from the kind of soul-numbing existence depicted here, the deep existential emptiness that Carol feels eating away at her from within.

0Awesome Comments!