The films of Wong Kar Wai are often about people who feel very intensely, who love and hate with a fiery passion that bursts out in the garish, expressive aesthetics of the films. In Happy Together, Wong examines this kind of passion especially intimately, through the gay relationship of Ho Po-wing (Leslie Cheung) and Lai Yiu-fai (Tony Leung), who visit Argentina together as a way to reinvigorate their on-again-off-again relationship, but wind up instead merely replaying the same troubles they always have. The film is a powerfully focused examination of this disintegrating, up-and-down relationship, capturing the violent emotions, the heartbreak, the longing and desire, and the fleeting moments of happiness that are like the glue holding this fractured romance together, momentarily bridging the gulf that's widening between these two men.

That gulf is represented, in many ways, by the waterfall at Iguaza, which they promise to visit together during one of their happier moments. The falls, seen on a lamp that Yiu-fai bought — a bright and gaudy representation of the falls, lit from within by a rotating cylinder that makes it seem as if the water is glistening in the sunlight — come to represent for Yiu-fai the potential for happiness and togetherness. This trip is something they planned to do together, a goal for their relationship, a sight they could share. Wong visually suggests that it's also an abyss that might swallow them whole. An image of the actual falls is inserted early on, as a response to the hopefulness that Yiu-fai has for the trip, but the image of the reality is very different from the lamp's sunny depiction of natural splendor. It's a sensuous color image of the waterfall, all dark blues and jungle greens, inserted into the mostly black-and-white opening section of the film. The camera slowly turns around the falls, capturing the slow churning of the water and, increasingly, the drifting white smoke that begins to fill the frame as Wong's graceful camera move pushes the tumbling water itself off to the sides. In stark contrast to Yiu-fai's optimistic desire to see this place with his lover, the image is dark and sinister, an image of destruction and apocalyptic grandeur: it is a seemingly bottomless pit, filled with smoke from the violent churning of the water as it crashes into the reservoir deep below. It's a gorgeous but foreboding image, a suggestion that what waits at the end of the trip is not reconciliation but erasure, heartlessness, brutality, the cold and cataclysmic violence of nature.

That image, so frightening and intense, lingers over the rest of the film. When that tracking shot of the falls predictably recurs at the end of the film, it provides a kind of melancholy closure, as one lover sees the falls in person, the water rushing down towards him, its spray drenching his face, while the other is left with the lamp, a gaudy and false facsimile of the real place. That's the essence of the film, the moment it's journeying towards, as Yiu-fai struggles against the confining boundaries of his unhappy relationship with Po-wing, a relationship where it's not clear who needs the other more, who's keeping who prisoner.

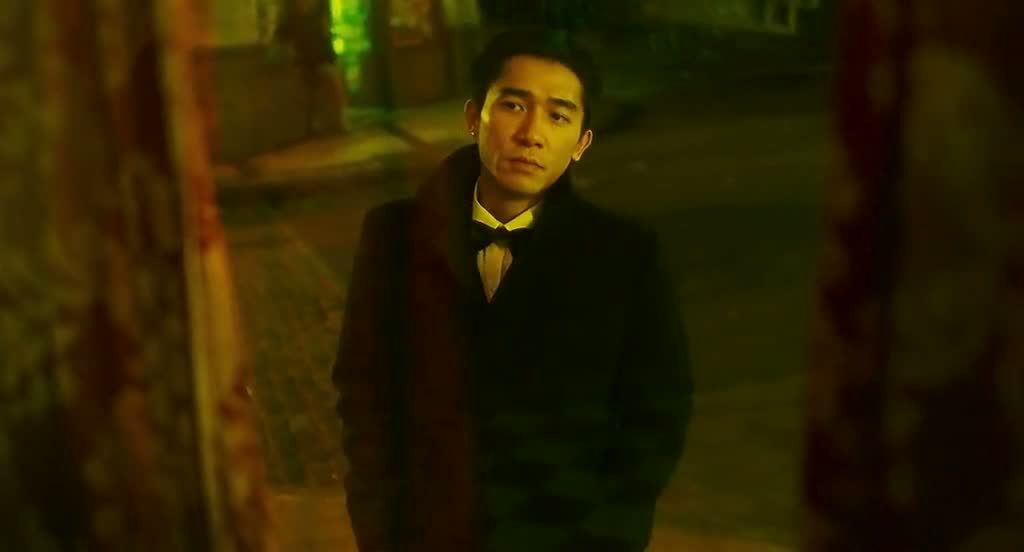

That dynamic plays out within some of Wong's most potent and beautiful images, as captured by his usual cinematographer Christopher Doyle. Though set mostly in Buenos Aires, Wong finds in this city a Southern hemisphere counterpart to his home base of Hong Kong, which perhaps explains the sequence where Yiu-fai, realizing that he is in the other half of the world from his home, imagines what Hong Kong would look like upside-down. The answer, as envisioned by Wong, is indeed turned upside-down but not otherwise that different, as he finds in Buenos Aires a similar late-night neon vibe, all hazy lights and poetically empty street scenes, occasionally interrupted by a bright, summery daytime scene where the sun fades the images to a white glare. That impression is introduced slowly into the film, as most of the early scenes play out in a crisp, high-contrast black-and-white, with only selected moments rendered in the characteristic warm, brilliant colors of the Wong/Doyle collaborations. When, after Yiu-fai and Po-wing are reunited following some time apart, the film explodes into full, sumptuous color during their cab ride back to Yiu-fai's apartment, it's as though the fullness of the couple's conflicted emotions have finally exploded to the surface of the film.

Despite these strong emotions, Happy Together is more relaxed and languid than previous Wong Kar Wai films, in which unpredictable violence could erupt at any moment, and this film looks forward to the slow, sensuous rhythms of In the Mood for Love rather than the the frantic tempi of most of the preceding films. The body of the film focuses on the lovers' uneasy reunion, as Yiu-fai tries to hold onto the unstable Po-wing, who obviously needs and cares for Yiu-fai but still can't help straining against the bounds of their relationship, going out, sleeping with other men, prostituting himself with American tourists. The relationship settles down slightly when Po-wing is beaten up by some of his clients for stealing a watch, and Yiu-fai tends to his lover during his recovery. The scenes of tension and arguing are offset by scenes of surprising tenderness and affection, like a sequence where Po-wing teaches Yiu-fai to dance, and the dance slowly becomes a gently swaying embrace. This scene, like the opening's disarmingly explicit and erotic sex scene between the men, establishes the stakes of their troubled love, the real depths of feeling upon which their often fractious relationship is built.

There's also tenderness in the depiction of Yiu-fai's friendship with his restaurant coworker Chang (Chen Chang), which is contrasted against the doomed love affair at the center of the film. As Yiu-fai's relationship with Po-wing collapses, his connection — platonic and hesitant, though not without suggestions of attraction and intimacy — with Chang deepens. Chang is a typically eccentric Wong character, a young man who had been nearly blind as a child and who had, as a result, developed extremely sensitive hearing and an ability to detect the smallest nuances of emotion in people's voices. He also, despite his displacement in South America, has the stability of home and family that the rootless Yiu-fai, wandering in a foreign land and disconnected from a family that's all but disowned him, only wishes he could someday return to. Those longings, the heartache and sadness of these aimless men, are expressed in typical Wong fashion. Chang carries a tape recording of Yiu-fai's tears to the "end of the world," a lighthouse in the far south of Argentina, where, it is said, his worries can be dissipated; it's a moment that looks forward to the similar scene at the end of In the Mood for Love. Po-wing also enacts the ritual of visiting his lover's apartment while Yiu-fai is not there, cleaning the place and rearranging things, a form of intimacy without direct contact that weaves through Wong's films.

Happy Together, like nearly all of Wong's films, is a deeply moving and rich work, a film about dislocation and the longing for stability. These characters have drifted far from home, isolated from their families and their homes, and they unsteadily try to make their way in an unfamiliar land even as their emotions overwhelm and unbalance them. Turned upside-down from their homes, they rush towards the churning abyss, towards the end of the world, and then pull back towards redemption and rebirth at the very last moment.

0Awesome Comments!