Abbas Kiarostami's Close-Up is a marvelously compelling documentary that, in the process of following the trial of a poor man accused of fraud, winds up delving into the nature of art and the relationship between fiction and deceit. The film is built around a real incident, the case of Hossain Sabzian, who impersonated the famous Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf in order to ingratiate himself with the Ahankhah family, pretending that he was going to film a movie in their home with the family as actors. The family was initially trusting but came to suspect him more and more, finally exposing him by inviting over a friend of a friend, the journalist Hossain Farazmand, who knew the real director by sight and instantly recognized that Sabzian was a fraud. Kiarostami's film is partially a documentary of the resulting trial, and partially a reconstruction — using the real participants in the events as actors, including Sabzian himself and the family he conned — of the events preceding Sabzian's arrest.

The film opens with a re-enactment of the reporter taking a taxi to the Ahankhah house to arrest Sabzian. Farazmand and the taxi driver sit in the front, while two soldiers sit in the back, and during this lengthy opening sequence the men chat casually, talking about the case they're going to deal with, about film, about journalism, and about incidents from Iranian history that happened in the areas they pass through. The conversation is casual and seems unrehearsed, though this is a re-enactment of the real events that led up to Sabzian's arrest. Once the cab arrives at the house, Farazmand goes inside, but Kiarostami's camera remains in the cab, observing as the driver chats amiably with the two soldiers in the back seat, asking them about their families and their homes. Then the soldiers go inside too, and again Kiarostami remains outside with the driver, as the man gets out of the car, picks up some flowers from a pile of trash, sniffs the flowers, and kicks an aerosol can so it rolls noisily down the street. The can rolls along the concrete, and Kiarostami's camera pans after it, eventually following it as the can starts to drag sideways across the ground in an unnatural movement, presumably pulled along by an unseen string from off-camera.

In this way, the subtle naturalism and observational aesthetic of the opening scenes gives way to a sense that things are being tweaked by the filmmakers, that not everything is necessarily as it seems. It's a reminder that the film's re-enactments are only playing at realism; they are in fact carefully arranged and scripted, based on real events but not in themselves "real" or unmediated. The naturalism of the opening is further deconstructed when, after Sabzian's arrest, the reporter remains behind, frantically running from door to door in the neighborhood to ask to borrow a tape recorder. The scene is farcical and surreal, as Farazmand rings doorbells at random, introduces himself, and asks for a tape recorder. One starts to wonder what kind of reporter shows up for a big story like this, planning to do an interview, and then has to beg for a tape recorder from complete strangers. It's comical and strange, especially when Farazmand finally gets his tape recorder and goes scurrying off down the street, pausing just once to give the aerosol can lying in the road a savage kick that sends it flying into the air, coming down and once again rolling along as the reporter disappears down a side street. As the credits finally roll, ushering in the meat of the subsequent film, concerning Sabzian's trial, Kiarostami leaves the audience to wonder about this strangely unprepared reporter, about con men, about reportage, about lies and fictions.

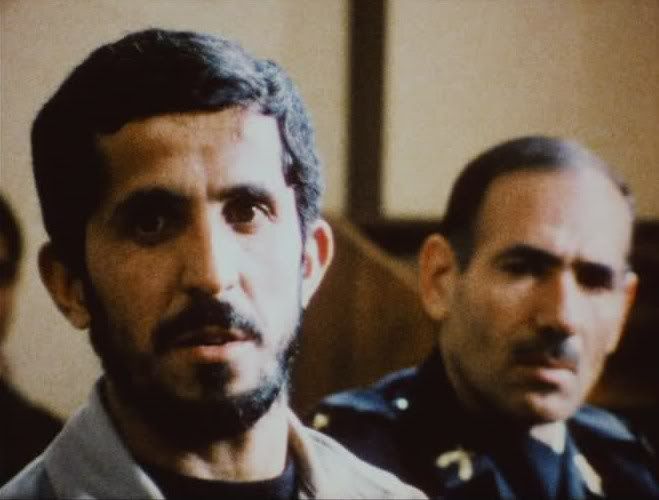

The images of the trial itself, captured in grainy footage that contrasts against the crisp, clean images of the re-enactments, are focused on Sabzian and his explanations for what he did. Kiarostami had remarkable access in the surprisingly relaxed courtroom where the trial takes place — or else not all of the trial footage is genuine, which only further blurs the film's interesting perspective on reality versus fiction, truth versus lies. Kiarostami seems too involved, too active in the trial's progress, for all of this footage to be real, unless Iranian courts are significantly less controlled than Western courts. The judge sits across the room, asking questions of Sabzian and the Ahankhah family, but for the most part Kiarostami's camera remains focused on Sabzian's face. At the beginning of the trial, Kiarostami explains to the defendant that this camera has a close-up lens and will remain trained on Sabzian, to capture his reactions and to provide him with a way to speak his mind and make his ideas clear. Kiarostami is making explicit what this film is about: he wants to give Sabzian an opportunity to express himself, to help others understand why he did what he did. During the trial, Kiarostami frequently even intervenes (or seems to intervene) in the proceedings himself, asking Sabzian direct questions and prompting the defendant to speak at length about the feelings and ideas that were behind his actions.

These close-ups of Sabzian are astonishingly moving, especially since the defendant's words reveal that he was no simple con man, that he was not trying to bilk the family out of money or otherwise exploit them. He did what he did, he says, because it made him feel respected. He is a poor man, divorced from his wife because of his inability to provide for his family very well, and he still struggles, constantly in and out of work, living a very poor and simple life with few real pleasures. His only pleasure, it seems, is the stimulation provided by the cinema, by art: he goes to the movies, especially the movies of Makhmalbaf, and finds a voice dealing with the kind of "suffering" that he himself feels in his own life. He is especially moved by the director's film The Cyclist, about which he says, "It says the things I wish I could express." With Kiarostami's prodding, the trial becomes a discourse on the purpose of art, the ways in which art can reach into people's lives in surprising ways. It becomes obvious that Sabzian impersonated Makhmalbaf because he wanted to feel as though he could reach people in that way, that he could express the things he feels with such clarity and beauty. As he struggles to express himself, to explain his actions, the subtext is the idea that art communicates. Sabzian's halting but often poetic descriptions of his "suffering," his poverty and feelings of uselessness and desperation, are a form of art, shaped and crafted by Kiarostami in turn.

The film is not only a commentary on the purpose of art but a subtle piece of social commentary as well, suggesting the hopelessness of poverty and unemployment that affects so many people. Even the Ahankhah family, who seem reasonably well-off in their large house, are not unaffected, as they have two sons who went to school for engineering, only to find that neither of them could get a job in the field after graduation. Instead, one son works in a bakery and the other is still unemployed. Sabzian's inconsistent work and constant struggles with money are even more extreme, and in court one of the Ahankhah sons, forgiving the defendant at the end of the trial, says that he blames "social malaise and unemployment" for Sabzian's actions. Kiarostami doesn't draw quite that straight a line between cause and effect, but it's obvious that he too thinks that this odd story is at least partially about class and economic hardship. Sabzian didn't commit his crime for money, even though he did borrow some money from the family at one point. He wanted to be Makhmalbaf not to get money, but in order to escape from his pathetic real life. He was playing a part and relishing the attention and respect he earned from the family who believed him to be a famous artist.

As he says himself at the end of the trial, at Kiarostami's prompting, he was more of an actor than a director, though. He was playing a part, he says repeatedly, and the structure of Kiarostami's film reinforces the connection between lying and acting, between the art of fiction and the art of the con man. The re-enactments in Close-Up, bringing together the real participants in these events to play out their scenes again, insert a further layer of fiction and artifice. In the reconstructions, Sabzian is playing at playing, pretending to pretend, while the rest of the actors are engaged in the same deceit. They play at reality, staging seemingly casual conversations that in fact are anything but unmediated. It is the flipside of the film's idea that art can reveal truths and speak to people about their own lives: art is also lying and pretending, and in that sense Kiarostami's film makes a very moving, strangely beautiful artist of Hossain Sabzian.

0Awesome Comments!