The title of Ingmar Bergman's masterpiece The Silence has multiple meanings, resonances that cascade through this puzzling, richly symbolic allegory. Bergman considered calling the film God's Silence, and the absence of divinity and spirituality is certainly one of the title's implications. This is particularly true since the film is the capstone of the so-called "faith trilogy," which cumulatively represents a process of moving further and further away from God, arriving here at a place where the deity simply doesn't exist and is indeed never even invoked. In many ways, however, it is fortunate that Bergman settled on a more ambiguous title, because the film is about much more than the absence of faith: it is about the myriad ways in which communication can fail, the ways that speech and language can drive people apart rather than bringing them closer to mutual understanding. At the center of the film are two sisters, one sensual and earthy (Gunnel Lindblom), and the other sickly, intellectual, and introspective (Ingrid Thulin). They are traveling to a strange and unfamiliar country with Lindblom's son Johan (Jörgen Lindström), while the convalescent sister grows steadily sicker, obviously easing towards death.

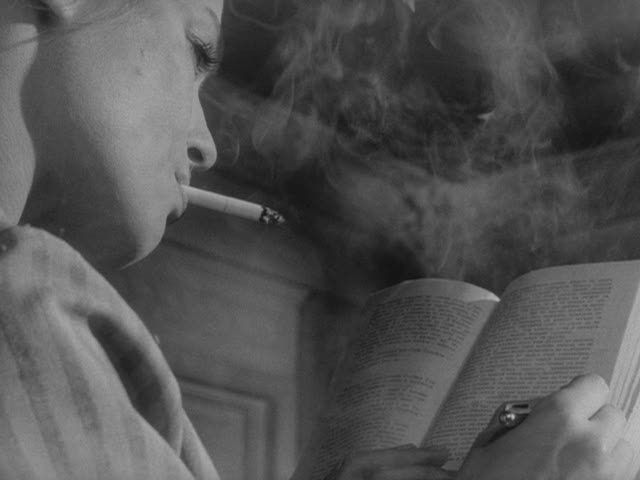

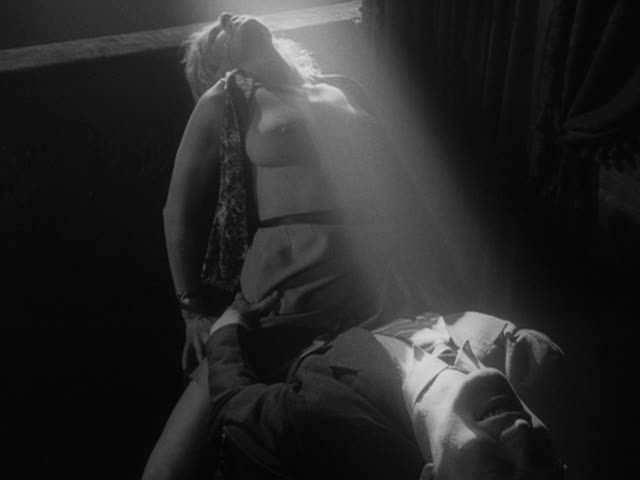

The film centers on miscommunication on multiple levels. The trio arrives in a country where they do not speak the language, and where war and social disorder (signified by the presence of tanks in the streets) seem imminent. Everything is breaking down here. While Thulin turns to books, music, and mechanically passionless masturbation to distract herself from her impending mortality, Lindblom indulges in sex and sensual pleasures. She is obviously a woman who enjoys her own body, and Bergman lovingly photographs her radiant skin and the beaded sweat that seems to perpetually stand out from her arms and neck. She has sex with a stranger, a man she can't even speak with because of the language barrier — their communication is limited to physicality and breaks down as soon as the act is over.

Meanwhile, Johan is the only one who, with his child's curiosity and wide, probing eyes, manages to foster some moments of limited communication within the strange, empty hotel where they're staying. As Johan wanders the halls, amusing himself away from a mother who keeps going off by herself and an aunt who's slowly dying, he meets a midget theatrical troupe who welcome him in as one of them, joyfully entertaining him for a few minutes before their gruff manager puts a stop to it. The boy also forges a tentative bond with the hotel's odd but kindly waiter (Håkan Jahnberg), a gangly old man who cheerfully mutters in his incomprehensible language while offering Johan food and companionship. Johan is a hopeful presence in the film, a bridging force who overcomes barriers to reach other people, but he is an exception to Bergman's bleak assessment of the possibilities of communication. Bergman is presenting a powerful political fable here: just as the relationship between the sisters collapses under the strain of their inability to make themselves understood to each other, so too do the relationships between countries falter and lead to war as communication is hindered. This is one of Bergman's finest works, a masterwork of despair that obviously inspired filmmakers as diverse as David Lynch and Stanley Kubrick, while retaining its own unsettling brilliance.

0Awesome Comments!