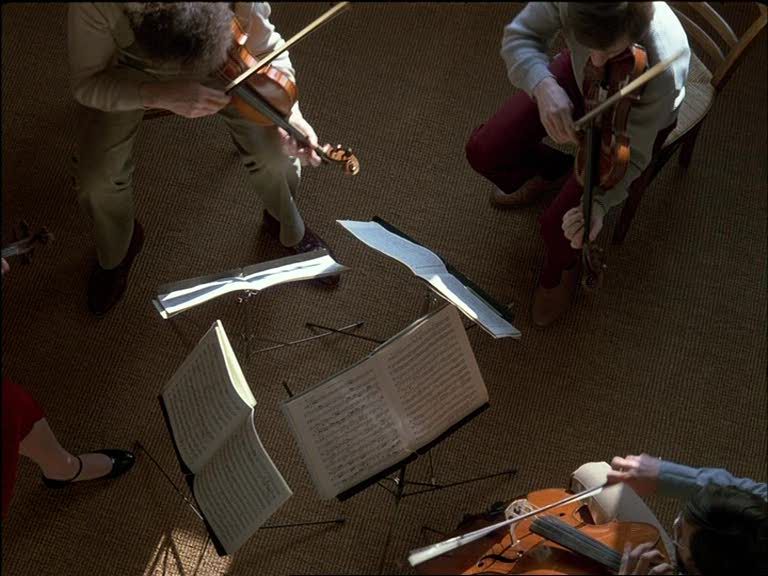

First Name: Carmen is one of Jean-Luc Godard's greatest films, a fragmentary retelling of the classic opera Carmen, with its tragic tale of the seductive title character (Maruschka Detmers) who earns the love of a soldier named Joseph (Jacques Bonnaffé) only to betray and discard her sensitive lover after not too long. Naturally, Godard uses the familiar story as a thin thread running through a film which would seem quite abstract without this narrative throughline to hold it together. The formal properties of cinema are laid bare, as they often are in Godard's films, and the soundtrack is particularly unpredictable, sometimes falling completely silent even when the characters are speaking onscreen, while at other times introducing non-diegetic sound to disrupt the reality of the image. Carmen's early line that she would like to make a film set near the beach is taken as a cue to introduce the harsh cawing of seagulls onto the soundtrack at random moments; Godard apparently liked the sound so much that he continued using it, with even less narrative justification, in many of his later 80s and 90s films. The soundtrack's construction is made a part of the film, as the narrative is intercut with scenes in which a string quartet rehearses the music for the soundtrack. These rehearsals are not only a typical metafictional intrusion, but provide an alternative narrative, complete with a heroine, the violinist Claire (Myriem Roussel), who becomes every bit as much of a character in this story as Carmen and Joseph. Even Godard is a character in the film, appearing as Carmen's half-crazy uncle, a retired director who now pretends to be sick so he can stay in a hospital; when the doctors try to kick him out, he solemnly promises to get a fever soon. Godard loves to cast himself in these kinds of slapstick parts in his later career, continually reminding his audience that he's the disheveled fool behind this chaos.

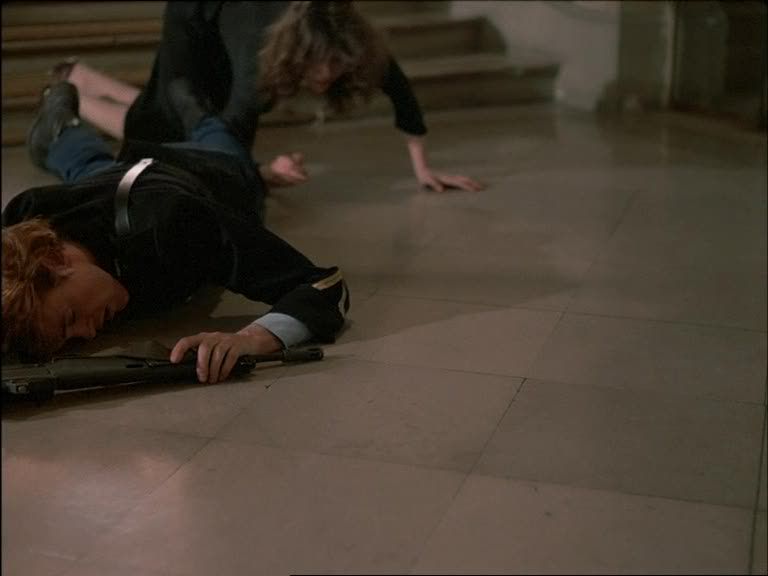

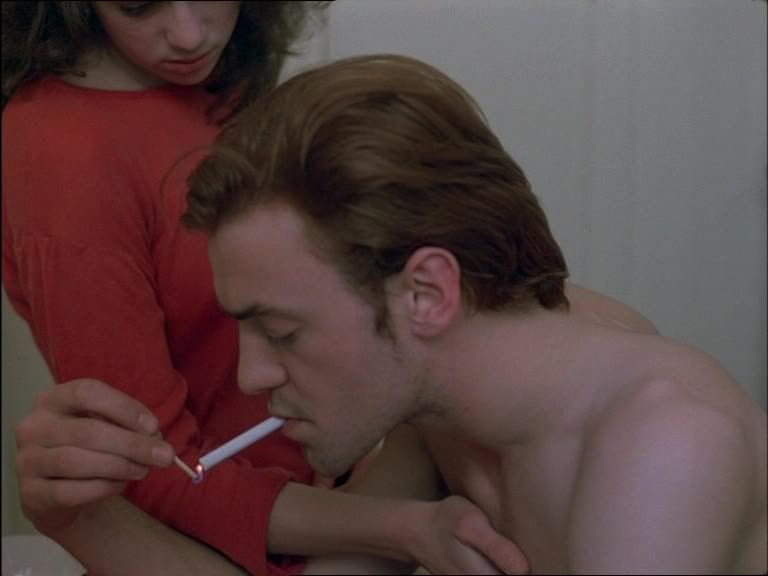

As for the central love story, the doomed romance of Carmen and Joseph, it proceeds in a series of isolated moments, broken up by Godard's frequent formalist diversions: cutaways to the ocean or the rehearsing musicians. Even when the lovers are onscreen together, their love seems transitory and fragmentary, split between periods of tenderness and furious altercations. Godard films them together in ways that abstract the relationship between them. They are often close, crowded together in the frame, but they can't quite connect. Their faces are turned at awkward angles from one another, or shadows obscure their expressions, or they turn away completely. In one infamous sequence, Joseph smokes and eats breakfast while Carmen sits nearby with no pants on, her bushy pubic hair directly in the frame's foreground while Joseph sits in the background, not looking at her. The film is about sex and disconnection, those perennial subjects for Godard, as well as the intimate relationship between passion and violence. The couple meets when Carmen is robbing a bank where Joseph is stationed as a guard, and their wrestling and fighting for a rifle changes abruptly into kissing. For Godard in his late period, cinema is still about a girl and a gun after all.

0Awesome Comments!