[This is a contribution to the Claude Chabrol Blog-a-Thon currently running at Flickhead from June 21 to June 30. For ten days, Flickhead will be dedicated to the works of the French New Wave master, and I'll be following along with many reviews of my own.]

In Que la bête meure, Claude Chabrol, interested as always in the mechanics of genre, engages with the form of the revenge thriller. Of course, Chabrol does not simply reiterate the staples of the genre, but digs into them, examines them, questions the basic assumptions underpinning these types of films. His plot is in many ways typical. A man loses a family member, who is killed by the carelessness of another. He is enraged, and when the police prove unable to do anything, unable even to find the smallest clue, he dedicates himself to discovering the man who did this to him. He vows to track down and kill this man even if it takes the rest of his life. It's a very stereotypical plot, the skeleton of countless revenge thrillers, a form that is perhaps even more circumscribed than other genres. But Chabrol's interest is in the details, in the moral ambiguities and problems stirred up by this clichéd story.

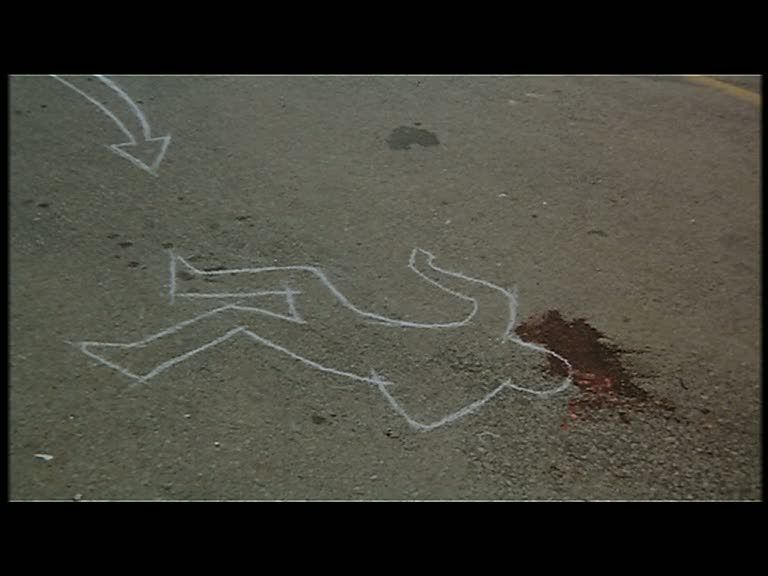

Charles Thenier (Michel Duchaussoy) has lost his son in an auto accident; the boy was mowed down crossing the street, and the driver simply kept going without pausing. No one steps forward to identify the car or its driver, no one knows of a car with its front bumper dented in. It is a mystery and the police are unable to get any further. So Charles, a children's book author, dedicates himself to tracking down the man who did this. Instead, by sheer chance he finds Hélène (Caroline Cellier), an actress who he believes was in the car that killed his son. Through her, finally, he discovers the identity of the man he has sought: the brutish, thoroughly horrible Paul Decourt (Jean Yanne), a garage owner and an utter monster of a man. As Charles describes him after their first encounter, Paul is "a caricature of the wholly bad man, such as one never imagines meeting in reality."

It's clear, then, that Chabrol is very aware of the manipulation of this genre, the way it stacks the deck, the way its details are carefully arranged to allow the audience to sympathize with murder. Charles is a basically decent man, unhinged by the death of a son he apparently loved greatly — in the opening scenes of the film, shortly after the accident, he tearfully watches home videos of the boy as he aged through the years. The man he is stalking, on the other hand, is a monstrosity, a man with no redeeming values, a man so despised by everyone he encounters that his own house grows hushed, dreadfully expecting his imminent arrival. Chabrol is quite aware of the artificiality of it all, the fact that this genre relies on the existence of a "wholly bad man," a man with no scruples, no morals, no trace of decency or likability or even humanity. He is hated by his son Phillippe (Marc di Napoli) and almost equally hated and feared by his cowed wife Jeanne (Anouk Ferjac). During a painful dinner scene at the Decourt family home, he embarrasses his wife by reading her poetry aloud in a mocking tone, much to the delight of his witchy, cackling mother (Raymone), the only human being who can stand her son's presence. When his son accidentally knocks over a wine glass, this oaf picks up food and throws it at the boy, ignoring his guests' horror. And he openly caresses his maid's legs and then castigates her for laziness, telling her, loudly enough for his wife and all their guests to hear, that just because he's sleeping with her doesn't mean she can loaf off.

He is every bit the "caricature" that Charles deems him, a man so thoroughly despicable that he could only exist in a movie, and even then most likely only as the villain of a story like this. It's all calculated so that Charles' inevitable murder of this man can be not only understand but cheered on, actively encouraged. Chabrol is too clever to simply buy into such conventions, though, and he's continually undermining the easy solution, adding complications that prevent the kind of clear-cut moral absolutism and justification for murder that such films typically offer up. Foremost among these complications is Hélène, who is overcome with guilt for her silence after Paul ran over Charles' son. She's basically a good woman, but self-conscious and delicate, easily thrown off balance, easily preyed upon. There's a certain tenderness between her and Charles, affection developing into quiet love.

Her presence distracts Charles from his goal and also awakens in him feelings more shaded and multi-layered than the all-encompassing hatred and desire for revenge that he feels for Paul. Charles begins the film as an emotional blank spot, desperately trying to suppress his emotions, to take control; in order to kill, he wants to be deadened, cool and calm. But his humanity reasserts itself in his relationship with Hélène. He allows himself to again feel something other than eviscerating rage and hatred; he cares for her. Soon enough, he comes to care as well for Paul's family, for the wounded son Phillippe, nursing his own bitter rage, and for the cringing wife Jeanne, who flits from one empty pursuit to the next in the hopes of finding some escape, no matter how shallow and momentary, from her domestic hell. His caring for these people does not dull his hatred for Paul — arguably, they only sharpen his resolve — but he does become a true man again rather than an empty shell, a hollowed-out action star whose only purpose is to enact brutality against an audience-sanctioned despicable target.

In pursuing this deconstruction of the thriller form, Chabrol's aesthetic is as precise and tightly controlled as ever. His camera traces careful arcs around the characters, turning neat 180-degree rotations that can bring characters together and sweep them apart just as easily. He favors both extreme closeups and distancing long shots, the latter generally used to accentuate the emotional chilliness of the bourgeois lifestyle he's chronicling. In one particularly devastating scene, Charles and Hélène arrive at a dinner party where no one can think of anything to say. Chabrol's camera frames them all in a long row, as formal as the Last Supper, while they chatter emptily, their talk littered with uncomfortable pauses; to find something, anything to say, they finally resort to enumerating the seasons and describing their beauty. But Chabrol's style can also be strangely intimate, as in a wonderful scene in which Charles and Hélène wake up in the middle of the night, their bodies tangled together in such a way that their faces, halved, seem to form a full face together, with one of his eyes and one of hers. It's a haunting image of two people coming imperfectly — but touchingly — together. Indeed, eyes are particularly important to Chabrol in this film. They are the focal point as well of the scene where Paul embarrasses Jeanne by reading her poetry. Chabrol pans around the table, capturing the distressed expressions on the faces of the guests, and finally finding the distraught Jeanne herself, her green eyes churning with anguish and hatred as her hands cover her mouth.

Chabrol is methodically dissecting the conventions of the revenge thriller here, and even his ending is deconstructive, hinting that the hero is going to walk off into the sunset, unpunished and vindicated, before pulling away from this cliché. Instead, the ending is a complex acknowledgment of the moral toll of murder, even "justified" murder, and of the necessity for culpability whenever a human life is taken. The film begins and ends with the waves of the ocean, transformed by context: at the beginning, they are markers of innocent childhood play, while by the end they are cleansing waters, washing away the guilt and sin of a man driven by revenge.

0Awesome Comments!