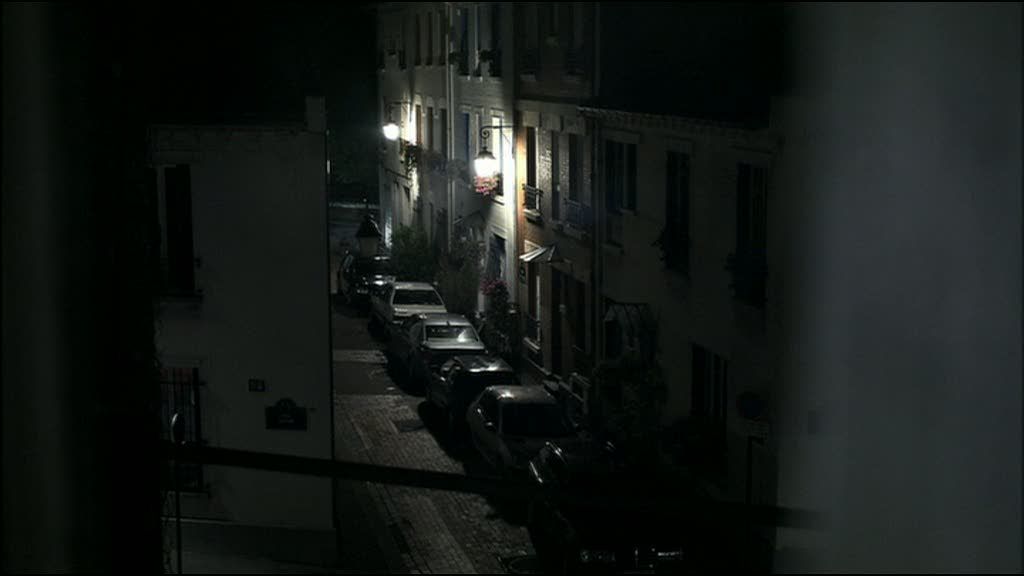

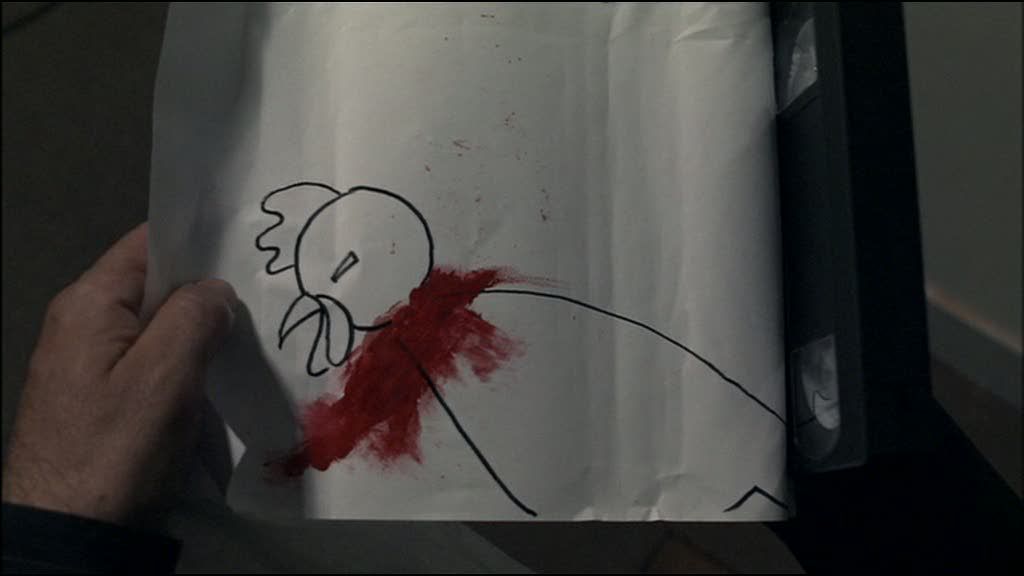

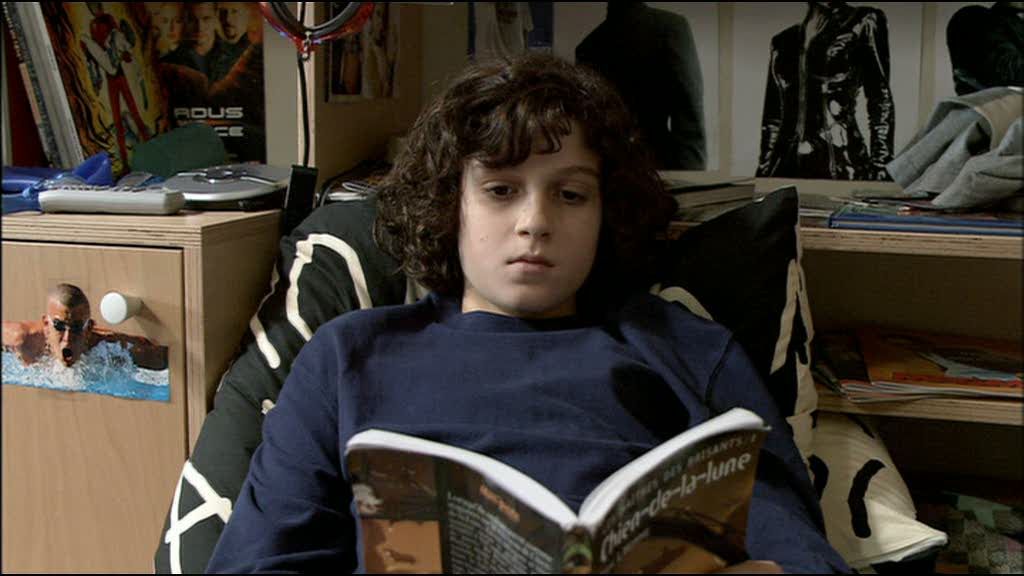

Michael Haneke's Caché boasts a thriller premise worthy of Hitchcock (or David Lynch, whose Lost Highway may have inspired the conceit). A French bourgeois couple, Georges (Daniel Auteuil) and Anne (Juliette Binoche), begin receiving mysterious videotapes at their home, tapes that mostly just show the exterior of their house in long, static views. The film's famous opening is a lengthy, silent view of a street scene, with eventually voices talking over it, expressing impatience that nothing is happening, a metafictional nod to ADD-afflicted modern cinema audiences. Only when the view is literally rewound is it revealed that this is a videotape, and that the voices are those of Georges and Anne as they try to figure out who sent this tape to them and why. This mystery drives the film, but it soon becomes clear that Haneke is not interested in providing a solution or treating this story like a conventional thriller. He's much more interested in the way this situation opens up windows into Georges' past, specifically calling up long-suppressed memories of an incident that occurred during his childhood. Through these videotapes, Georges reunites with Majid (Maurice Bénichou), an Algerian who as a boy lived for a time with Georges and his parents. Due to childish jealousy and insecurity, the young Georges told a lie that got Majid ejected from their family, essentially ruining the boy's chances for a better life beyond his immigrant status. This incident, nearly forgotten by Georges in his adult life, has never faded away from Majid's mind; he has nursed these wounds ever since. Haneke is probing at the intricacies of immigration and the failure of French political and social life to engage with the country's imperialist past, and especially the Algerian War.

As the videotapes keep appearing at Georges' door, his struggles become an allegory for the difficulties of dealing with issues of race, immigration and social status. For Georges, the past has been repressed. He has allowed his own actions to become remote from himself, to be dismissed from his mind, with little thought for the concrete effect that his childish lie has had on another man's life and opportunities. As a ward of an affluent white, native French family, Majid's life would doubtless have been much different than it turned out to be, and this is the central fact of the film, a fact that Georges is reluctant to address. But the videotapes increasingly make it difficult for him to avoid these uncomfortable truths. Haneke, always interested in media and documentation, sees video as an aid to memory, a way of confronting long-suppressed ideas. This is why his characteristic objective stance, embodied in his long takes and observational distance from his characters, is not cold or off-putting but paradoxically a way of getting closer to the truth, of not flinching away from even images that are difficult to watch and deal with. The film's notorious ending, in which the questions raised by the narrative are not resolved but left dangling in the most startling fashion, is not a dodge for Haneke. He wants to raise more questions than he answers here, to get people thinking about their own complicity in the routine injustices of the world. But he also wants to provide a measure of hope, as he does in the film's oblique final shot, which presents, hidden within its cluttered frame, a possibility of conversation and reconciliation, a suggestion that the crimes of previous generations can be addressed by the current generation.

0Awesome Comments!