Alexander Kluge's Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave is a film that probes just how difficult it is to understand the complex workings of politics and society, and to make a difference, when society and its structures are designed to eat up so much of a person's time and energy. The film's title itself implies as much: Roswitha (Kluge's sister and frequent star Alexandra) is the "domestic slave," a housewife who must divide her time between caring for her three children and her verbally abusive husband Franz (Bion Steinborn) and working to provide for them, leaving little time for thoughts or concerns outside of family life. The film is divided roughly in half, reflecting two different definitions of Roswitha's "part-time work." In the film's first half, she works as an illegal underground abortionist since Franz has no job and she must support the family. In the second half, after Roswitha's practice is shut down and Franz is forced to get a job, she becomes involved in social and political matters, trying to learn about the world outside her family. Her part-time work thus shifts, over the course of the film, from the need to provide for her family's physical and material needs, to the freedom and time to develop her own thoughts and ideas independently of the family. It is seen as an essential trade-off: when Franz isn't working, he's free to read and think, to study with no clear purpose in sight, but once he has to get a job he all but disappears from the film. By the same token, when Roswitha stops working, her mind becomes active and engaged, and she has time to develop an interest in things happening outside of the home, outside of her immediate scope.

What Kluge is interested in here is how segmented people's lives are, how people are forced, by society's demands, to split up their lives between home and work, unable to reconcile these two separate areas. Early on, the narrator intones, with deadpan irony, "to afford more children of her own, Roswitha carries out abortions." Roswitha, of course, doesn't see the irony, doesn't understand the profound contradiction between work and home contained in this simple statement. This announcement is followed by an extraordinarily detailed abortion scene, after which, once she's dumped the tools and the little blood-encrusted fetus into a metal pan, Roswitha takes a sip of tea and offers her patient a shot of liquor. It's all so casual, so offhand; it's obvious that Roswitha turns her mind off during these procedures. She's not in this profession for radical reasons, she's not doing it to help the women who come to her (though that's part of the rhetoric she uses when talking about it), she's doing it as a way to provide for her family, as a job like any other.

This all changes once police interest forces Roswitha to drop her profession, and Franz goes to work for the family instead. Roswitha, along with her friend Sylvia (Sylvia Gartmann), becomes involved in politics and social issues, though they aren't quite sure where to start at first. Their journey into these issues ranges from a distanced observation of official announcements and policies, to analysis of media reports, to trying to find understanding through art (they memorize a Bertolt Brecht song from a record), to finally becoming directly engaged and seeing things for themselves, hands on and face to face. It is, in essence, a journey into the world, struggling through the barriers and layers of representation erected by society, heading back into the direct experience of reality. Roswitha finds no satisfaction on an official tour of "the social situation," accompanying some politicians (almost all white, older men) as they spout rhetoric and she simply watches silently. She also finds no answers in the newspapers, because she quickly realizes that what she considers important issues — matters that directly affect people's families and children, matters that affect working conditions — are of no interest to newspaper editors, who reserve the front page for staid political news. Roswitha and Sylvia wind up storming out of a newspaper's office, enraged by the editors' inability to care about real people and their struggles.

Roswitha's struggle to understand, to have an impact on the world, eventually leads her to more direct, radical political engagement, trying to excite workers into revolting against unfair practices. Her engagement has its roots, as does everything for her, in the family: her husband's company is rumored to be shutting down its plants and moving to Portugal for cheaper labor, so she fears her husband will lose his job. From here, Roswitha becomes involved in labor and union negotiations, engaging in increasingly radical acts. She breaks into the company's offices looking for proof that they're going to move to Portugal, she distributes pamphlets to the workers, she meets with union leaders who seem to lack her passion and prefer a slow, steady approach. Finally, she goes to Portugal herself and sees the building site, with crates clearly marked with the company's name; she has her proof, because she has seen it with her own eyes. Kluge films this as a moment of peace and, almost, transcendence. There is a sublime hush as Roswitha stands in front of the crates overlooking a grassy field where, presumably, the new factory is to be built. This is the moment when Roswitha has come back into contact with reality, experienced directly and without mediation; she has seen it for herself rather than relying on documents or rhetoric or newspaper accounts or conflicting rumors. It is difficult to get to this point, Kluge stresses, but very much worth it; afterward, Roswitha smiles with genuine satisfaction, even before she knows if her work has actually made any difference. It hardly matters as much as the fact that she has shed her reliance on others and experienced something of significance for herself.

The balance between this engagement with the world and the demands of family is at the heart of the film. The idea that one's family is all that matters — stressed as a supreme value of society — can, for Kluge, actually be an impediment to caring about or understanding the wider world, to embracing and feeling empathy for the needs and problems of all people rather than just one's immediate family and friends. And yet Roswitha's social and political activism originates with the family: she is driven to make things better for her family, and to do so she must become involved in matters outside of the family. It is a central and irresolvable paradox, one that Roswitha never quite overcomes. For one thing, no matter how much she learns in her new ventures, no matter how much she accomplishes, she is never able to throw off the oppressive influence of her unappreciative husband Franz, who remains nasty and judgmental to the end.

Still, Roswitha is clever and inventive in making a place for herself outside the home, using her ingenuity to circumvent the strictures of a society that doesn't have much use for a woman outside of the home. In one of the film's funniest scenes — and as always with Kluge, there's a certain absurdist humor at work in his socio-political satire — Roswitha is confronted by police seals placed on the locks of her clinic. The seals read, "any unauthorized person tampering with these seals will be prosecuted," but this won't stop Roswitha. She pays a man for his dog, and lives up to the letter of the law, if not its intent, by having the trained dog open the door with its paws; thus, no person tampered with the seals. It's hilarious and absurd, and in many ways absurdity is what's required for someone who wishes to move within the confines dictated by this social situation.

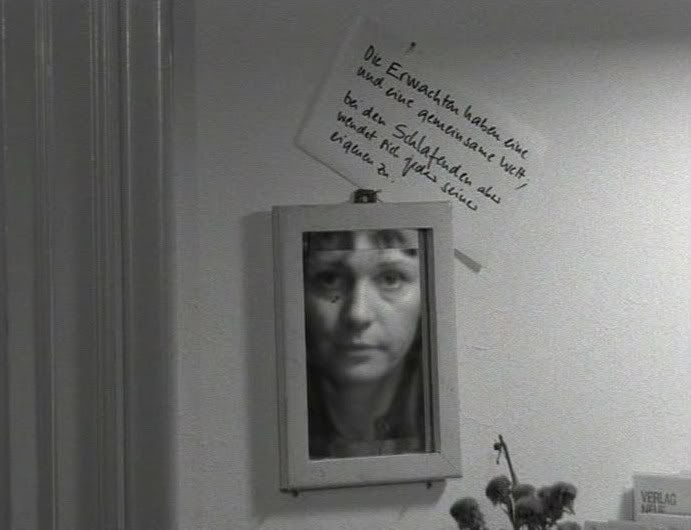

To this end, Kluge structures his film as a collage, incorporating paintings, clips of old movies, and interludes taken from children's storybooks, all of these inserted elements commenting obliquely on Roswitha's story. At the pivotal moment when Roswitha makes her decision to become involved in matters outside of the family, Kluge inserts a montage of shots of the wind blowing through branches or causing ripples in water: grainy and damaged images from older movies, poetically suggesting a change in the air. Some of the other film clips come from war movies, including one in which a soldier says that he can do anything, that's he essentially limited only by his lack of knowledge about foreign languages. These clips suggest that Roswitha lives in a man's world, where political matters are often decided by strong-willed men on distant battlefields, far from her prosaic world. Kluge similarly uses art and culture to define Roswitha's place within a long and perhaps overbearing cultural legacy: snatches of classical music frequently score scenes, while paintings show women as always being in the home, caring for children, doing domestic chores. Culture and society show no other options; Roswitha has to create them for herself.

0Awesome Comments!