Throughout the 1960s, Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci was searching for his own cinematic voice, experimenting in film and theater, working through his influences as he tried to find his own unique approach to his chosen medium. His debut film, La commare secca, was a neorealist noir with a script by his mentor Pier Paolo Pasolini, a work with only touches of the young director's nascent style. His next film, Before the Revolution, was far more personal, as he worked from the example of Jean-Luc Godard and the French New Wave to make a film in which politics and sexuality and psychology were intricately interwoven. His third film, Partner, was even more indebted to Godard, though in the years since Before the Revolution and the early 60s French films it had been inspired by, Godard had moved on, and Bertolucci tried to move on along with his idol. Partner is obviously derived from the example of Godard's late 60s political films, especially La Chinoise and 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, both of which loom large over Bertolucci's Godardian pastiche. Ostensibly based on the Dostoevsky story "The Double," Partner is actually an attempt to ape Godard's radical essay-film style.

It is, for the most part, an unsuccessful attempt. The film's obvious debt to Godard is distracting, as it's disconcerting to see a style as personal and idiosyncratic as Godard's adopted so shamelessly. Moreover, the film's appropriation seems shallow, limited to the superficial aspects of its source: what's missing is the complexity and density of Godard's thinking, and the corresponding lightness and dexterity he brings to even his most didactic and experimental films. Bertolucci's style is much heavier by nature, much more oppressive, and as a result Partner's theater of the absurd shenanigans come off as shrill and grating rather than whimsical. The film follows the theater professor Giacobbe (Pierre Clémenti) as his personality splits in two and he's haunted by a double who shares his name and appearance but who eggs him on to acts of provocation and violence.

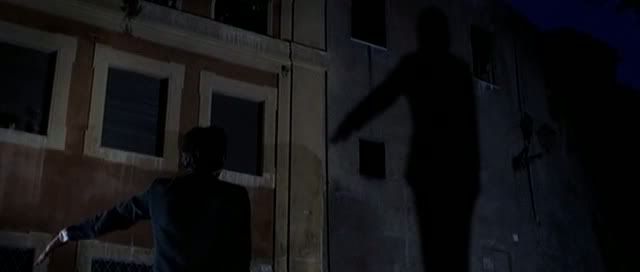

And that's about it for the film's story, which is utterly peripheral here, as Bertolucci simply stages one ludicrous set piece after another, a few of them entertaining or interesting but most of them rambling, intermittent exercises in what one character self-consciously deems "ham acting." The film's best sequences have a loopy charm that reveals Bertolucci's clever sense of humor and his subversion of expectations. In one scene, when Giacobbe is first starting to go crazy, he wanders through the streets at night, casting large shadows on the walls of the buildings lining the streets. At one point, he plays with a massive shadow projection of himself, performing mock salutes and military marches and watching as his shadow mimics him, cast up on the wall like a cinema projection. But then the shadow stops following Giacobbe's lead and begins marching on its own, and when Giaccobe hesitantly approaches the giant, it stomps on him and kicks him. It's a hilarious and visually provocative image of Giaccobe beginning to split in two, and also a metaphor for the loss of control over a creative work, which begins to function independently of its creator once it enters the world. If the film is about anything, it's about trying to find a creative voice, trying to find a way to express one's feelings about an absurd and violent world, and that image is one of the film's best and deepest.

Other sequences are simply a lot of fun, like a scene where Giaccobe and his servant/landlord Petrushka (Sergio Tofano, delivering a fun, clownish performance) steal a car but can't actually drive it, so they make sure to steal it at the top of a hill so they can simply roll it down. Later, when Giaccobe gets into the back of the car with his paramour Clara (Stefania Sandrelli), Petrushka "drives" by making humming motor noises with his mouth and pretending to steer. The film's best moments have that kind of sketch comedy verve to them, the willingness to be silly and goofy, to act like a clown. There's also the startling image of Tina Aumont as a detergent saleswoman with pale blue eyes painted onto her eyelids so that when her eyes are closed, she appears to be staring straight ahead, her gaze unblinking and eerie. The scene, with its giant detergent boxes and bold, colorful brand logos, is obviously derived from the very similar scenes in 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, just as Giaccobe's fortress-like piles of books in his apartment come from La Chinoise. Even the camerawork, with its graceful tracking shots and now-you-see-it-now-you-don't back and forth pans, is copied from Godard.

But Giaccobe's unhinged absurdities and non-sequiturs are a long way from Godard, and even at its best the film is slight and silly. One sequence parodies TV commercials with a jaunty ditty about cleanliness looping repeatedly as Giaccobe and the salesgirl frolic in the sudsy discharge of a washing machine, bathing in the suds, stripping and playing, alternately sexual and childlike, and ultimately deadly, all while that cheerful jingle plays over and over again in the background. In other scenes, Bertolucci subverts his own aesthetic by playfully messing around with the hidden split screen gimmicks that allow two iterations of Clémenti to coexist on the screen at the same time. The device is usually cleverly hidden, with the split obscured by dark areas or obstacles that disguise the split, but Bertolucci makes sure to reveal the trick, like a magician who can't help but excitedly exclaim how he did it even before the show is over. In one scene, the two Giaccobes have a conversation while one gets dressed and the other putters around nearby; they seem to be standing right next to one another, in the same space. But at a certain point one Giaccobe tells the other to hide, and the double on the right side of the frame begins walking left until, suddenly, he disappears into the hidden cut at the center of the screen, vanishing into thin air. Then, just to underline the point, the right side of the screen flashes with a light source that doesn't affect the lighting on the left side of the frame at all. It's Bertolucci's way of acknowledging the filmmaker's own complicity in this game of doubles and insanity.

The film's metafictional component becomes even more apparent in the finale, when one of the Giaccobes, ostensibly talking to his double, actually faces the audience and addresses them directly, calling on the viewers to get in touch with their own inner doubles, to be roused to action. It would be a stirring speech if the film as a whole had been more of a coherent call to action, rather than a confused blend of pseudo-philosophy and sloppy theatrical improvisations. Bertolucci's commitment to slathering the screen with messy, absurdist diversions sometimes yields interesting results, but more often the film fails to really delve deeply into the ideas it raises.

0Awesome Comments!